Moon Monday #201: Scientists can now study exotic Chang’e 6 lunar samples

Plus: New round of Chang’e 5 sample studies, gifting part of the Moon, and Sino-US cooperation

A note before we start: The Internet Archive was severely attacked recently. The non-profit’s free service archives public information from organizations worldwide, including those from space agencies and companies. Crucially, it enables journalistic access to dead or modified webpages. If any of the thousands of webpages I’ve linked to on Moon Monday disappear or morph at some point, you’ll almost certainly find an original copy on the Wayback Machine. While not a full-proof replacement of personal archiving, ensuring maximal public access to once public information is more important than ever for a democratic existence. I’ve donated to the Internet Archive, and I think you should too.

Scientists can now apply to study exotic lunar farside samples brought to Earth by Chang’e 6

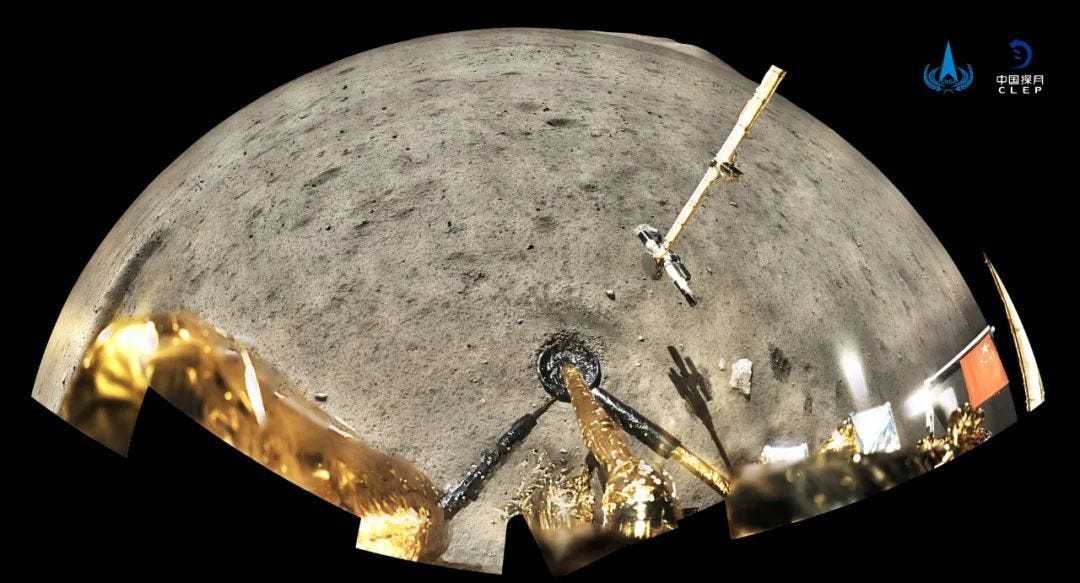

CNSA has opened up the first round of applications for scientists to study the first ever samples from our Moon’s farside, which were picked up in June this year by China’s Chang’e 6 mission and subsequently brought to Earth. Relatedly, CNSA also recently released lander instrument data—specifically from the landing & panoramic cameras, the mineral spectrometer, and the ground penetrating radar.

The 1.93 kilograms of Chang’e 6 lunar soil and rocks sampled from the large Apollo crater are scientifically even more valuable than the nearside Chang’e 5 samples since scientists expect it will help solve some long-standing mysteries about the origin, evolution, and volcanic past of Luna. Most crucially, the Chang’e 6 samples will help scientists understand why our Moon’s farside structure, composition, and landforms are enigmatically different than those on the nearside, something which has ties to better understanding the evolution of our Solar System.

The first round of applications to study Chang’e 6 samples is open to Chinese research institutions, who need to apply by November 22. Applicants can check high-level sample properties such as weight, particle sizes, and composition before sending in their proposals. To maximize scientific return from the samples, scientists from across China have been gathering in seminars and workshops to identify key themes to tackle. As per CNSA’s regulations, international researchers can send proposals to study mission samples two years after they’ve been brought to Earth. However, just like the case of Chang’e 5 samples, foreign researchers can collaborate with Chinese researchers to study Chang’e 6 samples as part of a team.

The opening up of Chang’e 6 samples for domestic research comes after the National Astronomical Observatories of Chinese Academy of Sciences (NAOC) completed storing the 1.61 kilograms of scooped mission samples in September. The process took NAOC scientists about two months because it involved carefully unsealing, size-sorting, characterizing, and then safely storing the samples in more than a dozen curated bottles, which now sit in a NAOC lab shelf right below rows of Chang’e 5 samples.

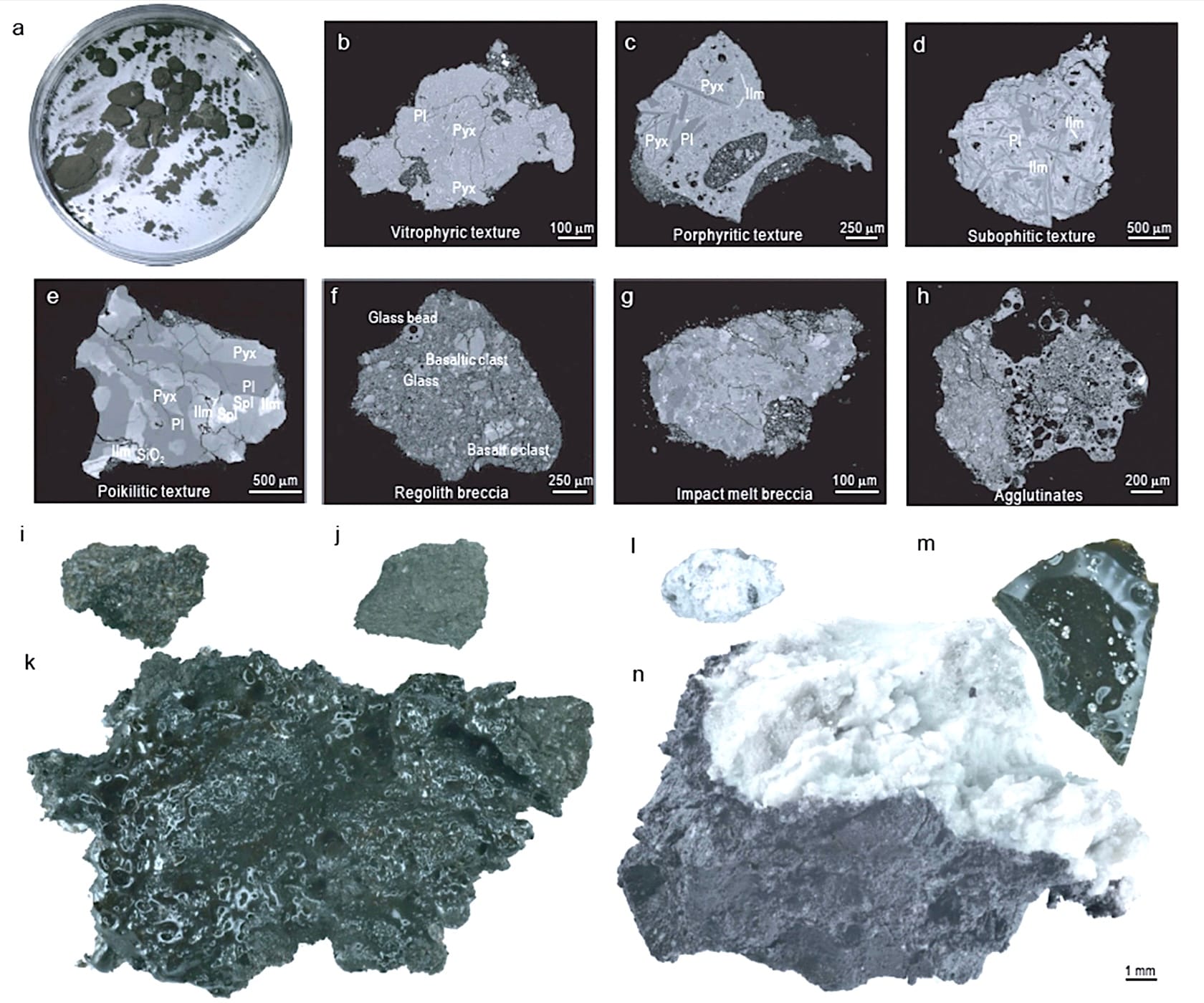

As part of that process, Chinese scientists also determined the broad physical, chemical, and mineral characteristics of the Chang’e 6 samples. As was expected, the samples indeed are very different than those fetched by past missions from the Moon’s nearside. The farside material as collected by Chang’e 6 has a whiter appearance, is less dense and more porous, contains more rocky highland material rather than bits and pieces from volcanic plains, and lacks heavier minerals.

CNSA had also said in September that for the remainder 325 grams of Chang’e 6 samples, which were drilled from below the lunar surface, scientists will need up to two more months to prepare, sort, and store them, after which the mission samples at large will be made available for research. And so that process is now presumably done. The drilled samples were to be segregated into 100 layers—one for every 1.5 centimeters of depth as found on the Moon.

P.S. The Chang’e 6 mission itself is not done yet. Continuing the trend, CNSA repurposed its orbiter module to enable future deep space missions.

Many thanks to Astrolab, Bethany Ehlmann and Tim Glotch for sponsoring this week’s Moon Monday! If you too appreciate my efforts to bring you this curated community resource, support my independent writing.

New round of Chang’e 5 sample studies, gifting part of the Moon, and Sino-US cooperation

In parallel to the opening up of Chang’e 6 sample research, CNSA has also started accepting the eighth batch of applications for studying the geologically young volcanic lunar samples brought to Earth by the Chang’e 5 mission in 2020. With a closing application date of November 22, these proposals can come from international researchers too.

Among its many discoveries, Chang’e 5 samples have helped scientists determine truer ages of lunar features, refine the nature of impacts over the last two billion years in the inner Solar System, and shed light on young lunar volcanism—which opened up more enigmas.

Banking on its achievement and value, China continues leveraging the Chang’e 5 samples to forge or enhance global partnerships. Last week, China’s leader Xi Jinping gifted Italy a gram of Chang’e 5 samples for scientific studies. In 2022, CNSA exchanged 1.5 grams of Chang’e 5 samples with Roscosmos for Soviet Luna 16 ones. Ling Xin reported in April 2023 that China gifted France 1.5 grams of Chang’e 5 samples, owing to their decades-long cooperation in space. Small amounts of Chang’e samples are also regularly on display at museums, conferences, and notable public events.

As of last year, less than 100 grams of the 1.73 kilograms of Chang’e 5 samples had been analyzed by more than a hundred research groups across China, many of which had international collaborators from several European countries, Japan, Australia, and even the US (as is possible multilaterally). Similar to how NASA has managed Apollo samples, China is saving the bulk of Chang’e 5 samples for future studies with ever-advancing instruments. CNSA will do the same for Chang’e 6 too.

Late last year NASA secured a remarkable exception from the US Congress for the country’s researchers to be able to apply to access and study Chang’e 5 samples despite policy and legal barriers. US scientists then applied for the same in April this year, including a proposal by lunar geochemist and Apollo sample curator Ryan Zeigler. Recent reporting partly based on comments by the NASA administrator Bill Nelson imply that the US and China are supposedly yet to finalize terms for US researchers to access Chang’e 5 samples and additionally potentially exchange lunar samples between NASA and CNSA. The only two reports to that end are based on too many undisclosed sources so it’s better to wait for official sources to clarify the progress and outcomes.

US scientists—and I, the non-scientist non-US lunar enthusiast—hope that NASA might be able to extend the US Congressional exception to study Chang’e 6 samples too. However, shortly after the Chang’e 6 samples arrived on Earth, both Victoria Bela and the Associated Press reported CNSA’s Deputy Director Bian Zhigang stating that the US remove legal obstacles like the Wolf Amendment to allow for regular Sino-US cooperation in space. The incoming US administration might make this prospect even more difficult.

More Moon

- Thailand is considering launching national Moon missions through a collaboration with ispace Japan. This step represents Thailand’s growing interest in exploring our Moon through strategic partnerships. Previously in April, the country joined the China-led long-term project to create a scientific base on the Moon’s south pole called the International Lunar Research Station (ILRS). This move came after Thailand’s largest space research organization, the National Astronomical Research Institute of Thailand (NARIT), joined ILRS in September 2023. As Ling Xin has reported, NARIT will fly a three-kilogram instrument duo on China’s upcoming Chang’e 7 orbiter to study solar storms and cosmic rays respectively. China aims to launch the Chang’e 7 lander and orbiter in 2026. The NARIT instruments will mark Thailand’s first study of Luna. NARIT also operates the Thai National Radio Telescope, which China might use to monitor spacecraft trajectories of ILRS missions in the future.

- In a talk at the Raman Research Institute, former ISRO Chief A. S. Kiran Kumar showed a new behind-the-scenes video on the making of Chandrayaan 3. His slides noted the year 2035 as the notional target for ISRO’s ambition to send an Indian crew around the Moon and back, a high point in an upcoming series of increasingly complex lunar missions starting with Chandrayaan 4 sample return.

- Related: The approach behind Chandrayaan 3’s triumphant touchdown on the Moon

- Next week I’ll be attending the ISRO-affiliated PRL institute’s MetMeSS planetary sample science conference in Ahmedabad, India. If you’re around, get in touch to chat all things space samples. 🤓